Postmarks of Great Britain & Ireland

Part 1 – Travelling Post Offices (TPOs)

CLICK HERE for a Bibliography of references to the TPOs of GB & Ireland

Before we can delve into the postmarks of TPOs, we really need to look at how TPOs came to be, and how they worked. But don’t worry, we’ll get to TPO postmarks further down the page!

In the beginning, before the railways …

In the early 1700s, a letter could take weeks – even months – to reach its destination … if it ever got there at all. In 1784, John Palmer of Bath introduced the first horse drawn mail coach, which also carried paying passengers.

This was a huge success. Many similar coaches were introduced, and for almost another fifty years mails and passengers were carried between the main centres of habitation in horse drawn mail coaches. The possibility of sorting mail in transit was considered, but rejected.

This was a huge success. Many similar coaches were introduced, and for almost another fifty years mails and passengers were carried between the main centres of habitation in horse drawn mail coaches. The possibility of sorting mail in transit was considered, but rejected.

The early railway years (before TPOs) …

However, this period of success was to come to a fairly abrupt end. The advent of the railways had a devastating effect on the mail coach services – on two counts. The railways drew much of the passenger traffic away from the mail coaches … thus depriving the mail coaches of a major source of income, and when the Post Office began sending mail by rail this was the death knell for most mail coaches.

Post Office mails were progressively transferred to the trains which at first more or less followed the same routes as the mail coaches (i.e. town centre to town centre). The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830, was the first to carry mail bags by train. This resulted in a considerable saving of time.

Procedures varied a lot over the years. What follows is a simplistic general guide only.

In the early railway years, bags of mail from sub-offices were taken to the local head post office or sorting office, where each letter or parcel would receive a postmark to indicate where (and usually when) that item had been received into the Post Office system. Any mail for local delivery was extracted and delivered locally. Any mail for routes using the remaining horse-drawn coaches was similarly extracted and sent by coach. All remaining mail (already postmarked) was sorted into bags destined for one of the major regions of the country, and then put on a train.

These rail-borne regional bags were taken to the major sorting offices throughout the country (later to be called General Forwarding Offices). At each of these major sorting offices, the incoming bags were re-sorted into bags destined for one of the various smaller district sorting offices within that region (later to be called Distribution Offices). At each of these smaller district sorting offices, the incoming bags were once more re-sorted and into bags for each Post Town (Head Office/Delivery Office) within that district … where they would be finally sorted into walks (i.e. the various streets along which each postman would walk and deliver the mail by hand).

Most people will have heard the saying The Mails must get through. For many years, this was taken to mean The Mails must get through by first post tomorrow! Each and every post office in the country had a Last Posting Time … before which you had to post your letter if you wanted it to get there by tomorrow’s first post. The more remote a post office was, the earlier its Last Posting Time was set at.

Remember that, so far, mail was first sorted and postmarked at the originating Head Office. Mail bags were transported by train, but were not opened or otherwise handled while in transit.

The First TPOs

By 1837 it was realised that extra time could be saved if, instead of sorting the mail at the head office and then putting it on a train, the unsorted mail was sent directly from the local head office and put on the train (to be sorted en route). An experiment was carried out in a carriage on a passenger train between Liverpool and Birmingham in the January of 1838 … and this was the birth of the Travelling Post Office (TPO). A TPO consisted of one or more specially designed carriages (manned by Post Office staff) attached to a regular passenger train.

[In the following discussions we must remember that, although the carriages used as TPOs belonged to the various railway companies and operated as part of trains run by these companies, the TPOs themselves were not controlled by the railway companies. TPOs were in fact controlled by a Post Office unit which became known as TPO Section in London.]

[You will also hear of carriages referred to as Sorting Carriages (SCs) and Sorting Tenders (STs). These had more or less the exact same duties as a TPO, but were controlled instead by provincial head post offices. Apart from the Highland Sorting Tender, all other sorting tenders became known as Sorting Carriages in 1904.]

As noted earlier, a TPO was really a Travelling Sorting Office rather than a normal post office. It should also be noted that Head Offices continued to postmark and sort any mails which could still be sent by train in time for tomorrow’s first post. Such mail continued to be sent by train in sealed bags just the same as before.

However, post offices now had the opportunity to set their Last Posting Time later in the day. Head Offices continued to apply postmarks to later mail, but they did not sort it. At the new later Last Posting Time, bags of postmarked (but unsorted) mail were taken to the TPO, where they were sorted in transit for delivery to one of the major sorting offices (there to be re-sorted for onwards transit).

By 1963 there were 49 mail trains running the length and breadth of the country. Some had just one TPO carriage, whereas others had up to 5 TPO carriages. There were even a few full TPO trains (consisting only of TPO carriages) running between London and Aberdeen and between London and Penzance.

Remember that mail sent to TPOs from Head Offices had already been postmarked at those Head Offices and showed no sign of its being carried on a TPO. Indeed, you will notice that, so far, we have made no mention at all of TPO postmarks. We’ll come to the postmarks shortly, but first we must mention the ‘Apparatus’.

TPOs and the ‘Apparatus’

Obviously, time was lost whenever a train had to stop at a station. The train had to stop at certain stations – stations where there were scheduled passenger stops, or stations were a lot of mail bags had to be dropped or picked up. However, there were quite a few stations where the train only stopped to pick up and drop a small number of mail bags. What was needed was some way of picking up and dropping a few mail bags at these stations without stopping the train.

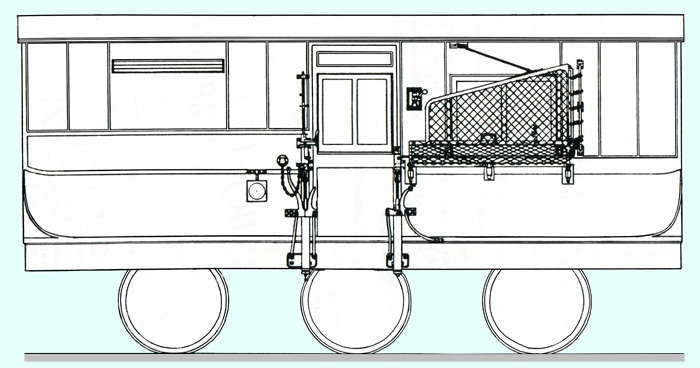

Work started on such an Apparatus in 1829, and continued for at least another 20 years before a satisfactory method was found. Below we see an 1860 carriage fitted with the Apparatus (based on an illustration from Harold Wilson’s book Travelling Post Offices of Great Britain & Ireland).

The Apparatus was really two separate mechanisms – one to let the TPO to drop bags off, and the other to let the TPO to pick bags up … with each mechanism having one part on the TPO and a corresponding part at the railside.

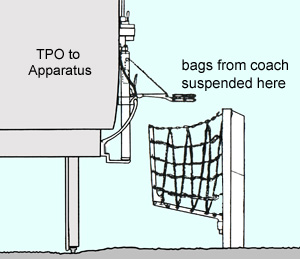

Bags to be dropped off from the TPO were suspended from a bar which swivelled out from the side of the coach, and were caught in a railside net as the train passed (below right).

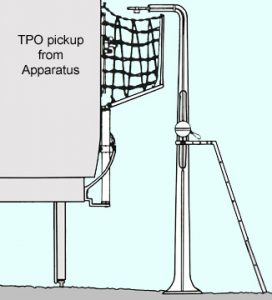

A few yards further down the line, bags to be picked up by the TPO would have been suspended from a railside bar, and caught in the TPO net as the train roared past (above right). The two mechanisms were designed to be at a different height so that they did not interfere with each other.

Mail transferred via the Apparatus was packed into special reinforced leather pouches to prevent damage. This pick-up and drop (or rather, drop and pick-up) procedure using the Apparatus was normally done at full speed, which resulted in a considerable saving of time. The procedure may look archaic, but it worked.

There is a demonstration video on youtube of the Apparatus being set up and a TPO subsequently going past at speed, dropping off and picking up mail bags.

CLICK HERE if you want to see the Apparatus in action

(opens in a new window – starts with an advert, but you can skip this advert if you wish)

TPO Postmarks

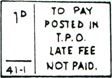

Of course, our interest in Travelling Post Offices is largely in their postmarks. Each TPO had a letter box in the side where ‘late’ mail (letters only – no parcels) could be posted. Such letters also required the payment of a ‘Late Fee’. This ‘late’ mail posted directly into the TPO (when it stopped at a station) was the only mail to receive a TPO postmark.

Each TPO had its own identifying postmark, and these widely varied postmarks gave rise to a whole new railway collecting hobby.

Some stations where a TPO stopped also had their own TPO ‘Late Mail’ Letter Boxes … which were cleared into the TPO when it stopped at the station. Mail from these station letter boxes was treated as being posted directly into the TPO.

TPO Postmarks – in the Early Years

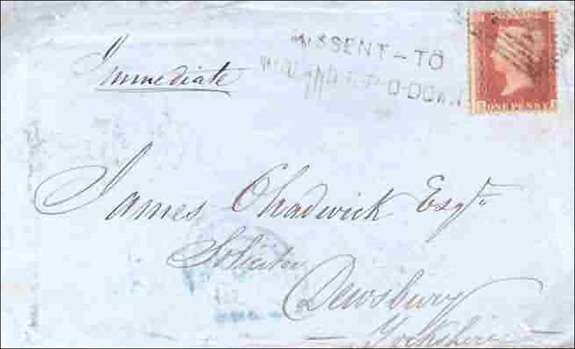

Some of the earliest known postmarks used by TPOs were mis-sent marks. Shown below is such a mark from the MIDLAND TPO DOWN, Bristol to Newcastle (‘DOWN’ meaning that it travelled in a direction away from the capital city, London). The mark is unclear, but reads MISSENT-TO/ MIDLAND-R-P-O DOWN. It was used on an 1856 letter from Bridge of Allan to Dewsbury and marked Immediate. From the date stamps on the back we deduce that the letter left Bridge of Allan on 3 November 1856, reached Newcastle on the 4th, and arrived in Dewsbury on 5 November 1856.

A display called About the RPG was presented at the 2017 RPG Annual Convention in Shildon. Part of that display covered Early Missent Postmarks. For more about Missent Postmarks

CLICK HERE to view the Early Missent Postmarks page of that display (opens in a new window)

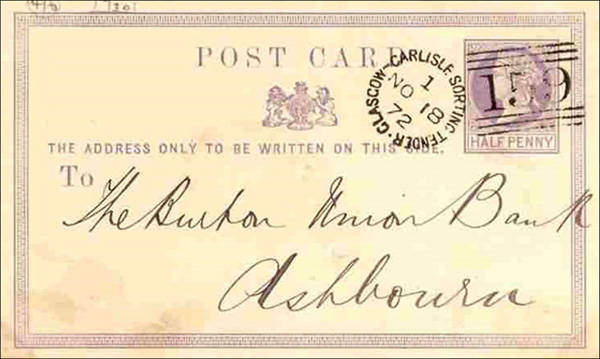

Not all TPO postmarks are identified by the text TPO. One of the postmarks most frequently found TPO postmarks is that of the Glasgow & Carlisle Sorting Tender (below). The train left Glasgow Central in the early evening and was a convenient service for the late posting of mail to the South. Shown here is a postcard addressed to a bank in Ashbourne posted on 18 November 1872. The postmark is a duplex (two part) mark with the Cancellation part showing the number 159 (for Glasgow).

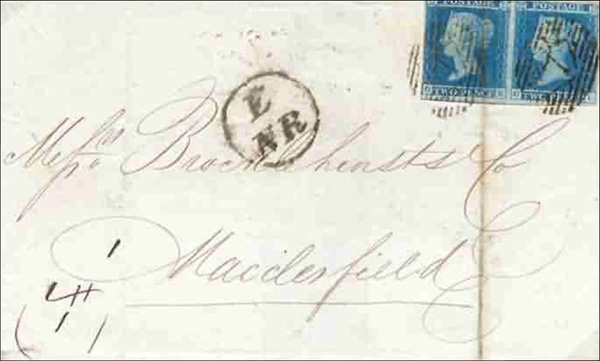

The interesting postmark on the envelope below (E/NR in a circle – Evening/Northern Railway) refers to the Grand Northern Railway, London to Preston. Although this mark indicates that the letter was sent to the TPO to be sorted (being too late to be dealt with in the ordinary way), the mark itself would have been applied at the Inland Office in London. This letter was sent from London on 16 September 1845 to Macclesfield, where it arrived the following day.

How do I classify / arrange my TPO postmark collection?

Well … that’s really up to you, but most collectors sort their TPO postmarks into TPO groups: that is, they arange all North Western TPO marks together, all London & Holyhead TPO marks together, all Great Western TPO marks together, and so on. Within each TPO group, collectors usually put all marks of the same type together … perhaps all single ring dated namestamps (srdn) together, followed by all double ring dated namestamps (drdn) etc.

In his book The Travelling Post Offices of Great Britain & Ireland Harold Wilson also organises TPO postmarks into TPO groups and illustrates over 1,200 different TPO postmarks – some of which have several varieties. Although now over 20 years old, this book is still the definitive reference text on TPO postmarks.

We therefore suggest that the most practical way to organise your TPO postmark collection is to sort them into TPO groups … and into types of TPO mark within each TPO group.

Here are a few miscellaneous examples over the years taken from Wilson’s book, assembled into TPO groups; each illustration is also accompanied by the Wilson reference number (e.g. W327c) plus the number of the page it appears on.

(Note that, although the date / time of any postmark will vary daily, any other changes show a different variety of postmark. Issue dates for the handstamps are give below where known.)

Caledonian TPO

issued 1848W632a (p. 169) | issued 1860W638 (p. 169) |  (used 1867)W642 (p. 169) |  (used 1952)W665f (p. 171) |  (used 1988)W665e (p. 170) |

Great Western TPO

issued 1902W340 (p. 113) |  (used 1929)W333 (p. 111) |  issued 1957W338h (p. 113) |  issued 1958W339a (p. 113) |  (used 1968)W346 (p. 113) |

London & Holyhead TPO

issued 1860W175 (p. 75) |  issued 1871W180 (p. 75) |  issued 1893W182a (p. 75) |  (not known)W184n (p. 77) |  issued 1934W184s (p. 77) |

North Western TPO

issued 1862W54a (p. 33) |  issued 1870W22 (p. 22) |  issued 1873W55 (p. 33) |  issued 1881W55b (p. 33) |  issued 1883W58 (p. 33) |

… but there are so many more! If you want to see many more examples of TPO postmarks and learn more about them generally, we recommend that you obtain a copy of Harold Wilson’s book.

AM Postmarks

Most British TPOs started their daily run before midnight on any particular day and used a handstamp with that day’s date on it. If the TPO run was scheduled to continue after midnight, the same date stamp (viz. with the starting day’s date) was used for the full run.

Thus, mail picked up further down the line after midnight was stamped with the previous day’s date. This enabled enthusiastic collectors to buy postage stamps at one of the ‘all day’ (24 hour) post offices in London just after midnight on their day of issue (i.e. very early in the day of issue), put them on first day covers, then drive to ‘down the line’ stations and post them into TPOs in the small hours of the morning. The postage stamp on the first day cover would then acquire a postmark date of the day before the official issue date for that stamp.

The Post Office (spoil sports that they were!) decided to close this loophole by issuing TPOs with an extra AM (After Midnight) handstamp to be used only on new-issue stamps. AM handstamps were first made available to TPOs for the Coronation stamp issue in 1953, but no examples of their usage on first day covers are know prior to 1960 (except in error). Such handstamps were much the same as the normal ‘operational’ handstamps, except that the date was set at the date of issue of the stamps(s), and the letters AM were placed just above the date. This, of course, resulted in a whole new set of postmarks for collectors to collect!

A display about what AM postmarks were (and some of the erors which occured) was presented by Dr Iain Wells (an RPG member) at the 2017 Convention.

CLICK HERE to view this AM Postmarks Display (opens in a new window)

Developments in TPOs

The success of the early TPOs had the expected result – more and more TPOs were set up over a widening TPO network. By 1850, some 40 or so Post Office staff were employed on TPOs running on a multitude of lines between Perth and Exeter. By 1867, there were 200 members of Post Office staff working on TPOs.

There were two ‘flavours’ of TPO – Night Mail and Day Mail. By and large, the Night Mail TPOs carried late-collection mail from London, for tomorrow’s morning delivery in the provinces (‘down’ services, away from the Capital), and carried late-collection mail from the provinces, for tomorrow’s morning delivery in London (‘up’ services, towards the Capital). The Day Mail TPOs carried tended to deliver mail in time for afternoon deliveries.

By the early 1900s (before the first World War), there were more than 130 TPOs running the length and breadth of the country.

In 1968, the Post Office introduce a two-tier postal system – first class letters (to be delivered by tomorrow’s first morning post), and second class letters (to be delivered later – usually by tomorrow’s afternoon post). At this point, a decision was made only to sort first class letters on TPOs.

What vehicles did a TPO consist of?

A TPO was made up of one or more Post Office Sorting Carriages. Many TPOs also had Post Office Stowage Vans or Bag Tenders for carrying sealed bags of sorted mail. There were sometimes other miscellaneous Post Office vehicles such as Brake Vans, but we will ignore those here.

Most TPOs ran as part of a normal passenger train. There were four Special TPOs which were made up of only Post Office vehicles, mainly Sorting Carriages and Stowage Vans, and had no passenger carriages. The Specials were:

• The Up Special TPO (Aberdeen to London)

• The Down Special TPO (London to Aberdeen)

• The Great Western TPO Up (Penzance to London)

• The Great Western TPO Down (London to Penzance)

In its prime, the Up Special could consist of six Sorting Carriages plus eleven Stowage Vans, making it the longest TPO in the world!

CLICK HERE to see the 1958 schedules for the TPO Up Special and TPO Down Special

(opens in a new window)

Sorting Letters & Parcels on a TPO

(What follows applies to vehicles described as TPOs, Sorting Tenders, Sorting Carriages etc.)

In a typical TPO carriage (Sorting Tender/Sorting Carriage), one side (we will call it the right hand side) was set up for sorting letters and parcels, and the other side (we will call it the left side) was for storing the sorted letters and parcels.

On the right hand side there were Sorting Frames (sets of pigeon holes into which letters were sorted), and larger frames (called Desks) for sorting parcels and larger letters. Each pigeon hole had a sort address written on the top … either hand-written in chalk, or on changeable flexible ‘fillets’ with sort addresses on them. On some Sorting Carriages the pigeon holes were just numbered.

On the left side of the carriage there were rows of hooks to hold mail bags – into which the sorted letters and parcels were deposited. The top of each bag was usually held open with a wire loop to make it easy to drop letters or parcels into it.

When a bag was full it was sealed and labelled (with its target address) and taken out of the Sorting Carriage into an adjacent Stowage Van, ready for dropping off at the appropriate station or sorting/delivery centre. The left side of the carriage also had a rack above where a supply of empty mail bags was kept.

Shift Working on TPOs

Some TPOs had more than one Sorting Carriage. Depending on the size of the TPO, it could be staffed by anything from 4 to 40 Post Office clerks. The shift pattern of a Sorting Carriage clerk was somewhat disruptive. Here is a typical weekly schedule for a Post Office clerk working on a TPO (the times quoted would vary depending on the location and routes of the TPOs):

Monday. Take a passenger train to a distant location. Catch a TPO back ‘home’ from the distant location at 8.30 pm (or there abouts), arriving ‘home’ at 3.30 am (or there abouts) on Tuesday morning.

Tuesday. Get some sleep at home. Catch (say) an 8.30 pm TPO to a distant location, arriving at the distant location at (say) 3.30 am on Wednesday morning.

Wednesday. Lodge and get some sleep somewhere local until it was time to catch (say) the 8.30 pm TPO back home, arriving home at (say) 3.30 am Thursday morning.

Thursday. Get some sleep at home. Catch (say) an 8.30 pm TPO to a distant location, arriving at the distant location at (say) 3.30 am on Friday morning.

Friday. Lodge and get some sleep somewhere local until it was time to catch (say) the 8.30 pm TPO back home, arriving home at (say) 3.30 am Saturday morning.

Today, we would call these antisocial hours. Obviously, it did not suit a lot of people. Yet there were staff who worked TPOs for a full 40 years!

How about a Bonus?

If you have read this far, you deserve a little bonus before we get to the bad news! How about watching the 1936 film Night Mail. It is 23 minutes long and very atmospheric, with music by Benjamin Britten, and contains extracts from WH Auden’s poem The Night Mail.

CLICK HERE if you would like to view The Night Mail

(Opens in a new window. You then need to click the Watch For Free button {bottom right}, then click the I accept this guidance button on the U Certificate {centre screen}).

And now the bad news …

The Decline and Fall of the Travelling Post Office

But the writing was on the wall! Improving roads and improving road delivery services gradually lessened the benefits of sorting mails on TPOs. At first, the smaller, less profitable and marginal TPOs were withdrawn. Then, as competition became more fierce, more TPOs fell by the wayside.

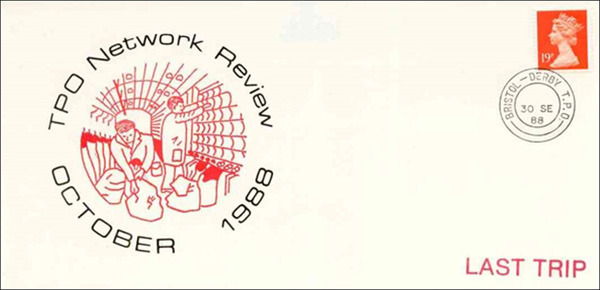

Worldwide, every major country had a comprehensive network of TPO routes. Few of those still survive today, and their days are probably numbered. Back home, here below is a special cover to mark the last run of the BRISTOL to DERBY TPO on 30 September 1988.

By the late 1990s, only 10 major British TPOs were still running, although such was their size that it took 370 Royal Mail staff to work them. All good things come to an end, and so it was that in 2004 the last TPO made its last journey.

Of course, there is much, much more you can learn about Travelling Post Offices – we have only scratched the surface here. Why not make a start on collecting TPOs now?

If you want to know more about Travelling Post Office postmarks the definitive work on this subject is The Travelling Post Offices of Great Britain and Ireland – Their History and Postmarks written by H.S. Wilson and published by the Railway Philatelic Group (ISBN: 0 901667 23 4) (available via the RPG Publications Officer at publications@railwayphilatelicgroup.co.uk ). If you get bitten by the TPO bug, you really need a copy of this book!

CLICK HERE for Postmarks of Great Britain & Ireland – Part 2, Railway Station Postmarks